(Updated) Xapo subject of fraud lawsuit filed by LifeLock

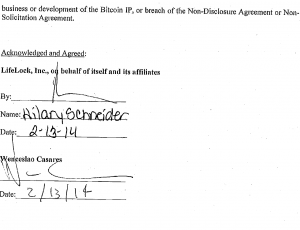

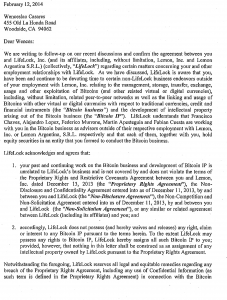

Update: CoinReport has received, from Xapo’s communications agency, The Hatch Agency, a copy of a letter from LifeLock President Hillary Schneider which acknowledges that LifeLock has no claim.

The copy of the said letter:

Moreover, Steven Ragland, attorney representing Wences Casares, has issued the following statement:

Moreover, Steven Ragland, attorney representing Wences Casares, has issued the following statement:

“This is a baseless lawsuit. LifeLock has no right to any Bitcoin related business or IP that Wences Casares or his colleagues may have worked on during their time at Lemon or after. As LifeLock’s President has attested in a legally binding document, LifeLock does not have any right, claim or interest to any Bitcoin IP. LifeLock’s claims lack merit and we look forward to proving their allegations false.”

—

Fortune has reported that Bitcoin company Xapo is the subject of a previously-unreported fraud lawsuit filed by LifeLock, an online identity security company.

In December 2013, LifeLock paid more than $42 million to acquire Lemon, a digital wallet led by eventual Xapo founder Wences Casares. LifeLock alleges that Xapo was founded “using a product developed by Lemon employees, in Lemon’s facilities, on Lemon’s computers, and on Lemon’s dime.”

The suit names Casares and four other Xapo employees, all of whom had worked at Lemon, as defendants. While Xapo itself is not named, LifeLock is asking the court to require Casares, et al to disgorge “the value of the Xapo product attributable to Defendants’ misrepresentations, omissions, breaches of duty, and other wrong conduct,” reported Fortune. The magazine said LifeLock, which has an extensive history of being sued itself, could be buoyed to file its next complaint directly at Xapo.

Fortune reported that according to LifeLock, Lemon initially started work in April 2013 on a Bitcoin product to be integrated into its main digital wallet offering. But the company’s board of directors terminated the project as merger talks with LifeLock were starting. It’s not clear whether the board’s actions and merger talks were connected, but LifeLock says it declined an early offer to only take over the digital wallet app, which would have allowed Casares to “continue developing a bitcoin business.”

Both parties worked out a deal for Lemon as a whole in mid-September, with the transaction closing three months later. Lemon was valued at $42.6 million, although $5 million of that was put into an escrow that LifeLock would later claim for performance matters not related to the lawsuit. Fortune reported there is no mention in the merger deal of a carveout for Bitcoin IP.

LifeLock states it knew Casares had built himself a “personal” Bitcoin storage vault, but he told the board other investors were asking to store Bitcoin with him, and asked for “a letter from LifeLock acknowledging that it would not stake claim to Casares’ bitcoin storage vault or their bitcoins, and thereby place their investments at risk.” Casares then requested similar letters for five other Lemon staff members, two of whom were part of an Argentinian subsidiary, to which LifeLock denied the request, “expressly telling Casares that no other Lemon employees could work on his personal storage venture.”

In its complaint, LifeLock said, “Casares then claimed that those individuals were also investors and that he simply wanted an acknowledgement that they could be investors and provide strategic advice. Casares agreed that under no circumstances would those individuals perform day-to-day work and, indeed, would provide nothing more than strategic advice for what LifeLock understood to be Casares’ personal bitcoin storage business that he intended to offer to other wealthy Silicon Valley investors.”

Fortune reported that LifeLock provided the letters, referring to the five other Lemon staff members as “strategic advisors” and “investors.” On March 6 2014, Casares presented four of the five letters for signature to LifeLock’s president, Hillary Schneider. Shortly after the documents were executed, Casares submitted his resignation.

The magazine said that given that LifeLock still purportedly thought Casares was just working on his pre-existing Bitcoin storage vault, it asked him to stay on “through an orderly transition and Casares agreed to delay his departure in order to do so.”

On March 13, Casares announced the launch of Xapo, backed by $20 million in venture capital. In an interview with the New York Times, Casares said Xapo’s team included three individuals who, at the time, were still full-time Lemon/LifeLock employees. One of those team members, Frederico Murrone, had received one of the acknowledgement letters, which Fortune reported that it learned did refer explicitly to “any IP related to bitcoin.”

Lemon immediately started investigating, which included interviewing staff (excluding Casares, who refused) and forensically imaging all Lemon computers and servers, including those in Argentina. It alleges to have discovered proof that Casares and his fellow defendants had kept developing Lemon’s Bitcoin technology “in secret” long after the board had ordered it to stop – in the Lemon offices, on company computers, “during Lemon-paid business hours.” Fortune noted that an app featuring the Xapo logo and brand quietly launched on Google Play just six weeks after LifeLock acquired Lemon, and more than a month before Xapo’s formal launch announcement.

According to the complaint, “forensic analysis of Defendants’ computers also revealed presentations that Defendants had authored for potential Xapo investors during the time they were employed by Lemon, detailing the bitcoin wallet functionality of the app. One of these presentations touted the fact that ‘Xapo offers both a wallet and cloud-based cold storage’ and that Xapo would offer ‘seamless 1-click transfer from Wallet to Vault.’ The document’s metadata indicates that it was last modified on February 4, 2014 – months after LifeLock’s acquisition of Lemon. Electronic artifacts on Casares’ computer indicate that Casares too had had Xapo-related files on his Lemon computer going back to December 2013, but that Casares deleted those files from his Lemon computer shortly before tendering his resignation.”

The complaint also alleges that Lemon general counsel and current Xapo President Cynthia McAdam, who is also a defendant, “often claimed the need to work from home,” but actually working on Xapo business from Xapo’s Palo Alto office.

Fortune reported that McAdam’s Lemon contract expired the same day the New York Times article was published, and Lemon soon terminated for cause three remaining staff members believed to be Xapo employees, including Murrone. It negotiated with Casares for almost four months before terminating him for cause on August 1, 2014.

Lemon then filed its suit last October. The defendants have yet to file a formal response, but Casares and McAdam have filed a motion to dismiss. The motion concentrates mostly on the acknowledgement letters, with Casares arguing that he was indeed given room to work on Xapo. The defense asserts that Lemon is making an arbitrary distinction between Xapo “employees” and “advisors,” writing:

“In Defendants’ industry, it is not uncommon to describe persons collaborating on a project as advisors – indeed, even Steve Jobs was reportedly brought in as an ‘advisor’ to Apple when he returned to that company in 1997.”

Fortune reported that recent court filings show that the “discovery” period could start soon, although it is far too early to determine whether the case will go to trial.

The magazine said the lawsuit threatens both Casares’ reputation and his company’s intellectual property. While the company is well-funded with big-name advisors, it has had its recent issues, among them failed bank relationships.

Casares has not commented on the lawsuit on record, nor has Xapo made a public comment. Fortune reported that Casares did not mention the litigation to its three new advisory board members, or at least not until the magazine started making calls.

People close to Xapo insisted to Fortune that even if Casares were found guilty, it would not hurt the company. But that may be a stretch, said the magazine. If LifeLock wins its case, Xapo – a financial services firm – would have a CEO who was convicted of civil fraud.

Image: File photo

Xapo does not allow access to my Bitcoins

Two years ago I bought Bitcoin. Now Xapo changed the App. After approx. 50 load ups of the International ID the App still requests to do it over and over. The Xapo Support apologized in the beginning. After 3 Weeks now no more reaction at all.

Xapo offers on the homepage to transfer the money to any other provider if the App does not work.

My question is: “Does anybody have experience by transferring the coins that way?” Cause I believe the coins then will be gone…

Thank you for any help/idea how to get the coins back.