ShellShock, HeartBleed, and Bitcoin: Why Security is Bitcoin’s Biggest Hurdle

For the second time this year, awareness of a massive security vulnerability has run rampant across the Internet, reaching such scale that the public at large has become aware of it. In April, it was “HeartBleed,” a vulnerability in the OpenSSL cryptographic software used across the Internet. Right now, it’s “ShellShock,” a vulnerability in Bash itself, a piece of command line software that’s virtually ubiquitous across machines running any derivative of Unix, including OSX and mobile operating systems like Android. It’s the worst, broadest security vulnerability in living memory. Both vulnerabilities, under certain circumstances, can allow outside attackers to gain access to your computer or phone and do pretty much whatever they want.

For the second time this year, awareness of a massive security vulnerability has run rampant across the Internet, reaching such scale that the public at large has become aware of it. In April, it was “HeartBleed,” a vulnerability in the OpenSSL cryptographic software used across the Internet. Right now, it’s “ShellShock,” a vulnerability in Bash itself, a piece of command line software that’s virtually ubiquitous across machines running any derivative of Unix, including OSX and mobile operating systems like Android. It’s the worst, broadest security vulnerability in living memory. Both vulnerabilities, under certain circumstances, can allow outside attackers to gain access to your computer or phone and do pretty much whatever they want.

This has implications in a lot of circles (from privacy – see the recent massive theft of celebrity pictures – to corporate espionage), but one of the most pressing areas that it affects is Bitcoin, and is arguably its biggest roadblock right now. I’m not talking about mass adoption: there, the biggest issues there are probably how difficult the actual Bitcoin software is to use, and the hard problem of merchant adoption.

I’m talking about, for lack of a better and less dramatic word, the “dream” of Bitcoin: the idea that Bitcoin might one day enable a financial world that does not depend on central institutions that can impose their will on peoples’ lives through it: a world in which people’s money is cryptographically secure, hidden from prying eyes and thieving fingers. Right now, that dream is in danger, because the computers that we use are so vulnerable to hackers. The advantage of centralized systems is that the moderators of those systems can intervene when a mistake is made or theft occurs and, if they evaluate the system correctly, right the wrong. If your credit card is stolen, you don’t actually have to worry too much about losing your life savings. The same is not true of Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies. Because the system is decentralized, there’s nobody to hear your pleas and right your wrongs. Bitcoin is a currency with no guard rails, no second chances. If you misplace the decimal point or mistype the address and accidentally send $300,000 to the wrong address, you’re simply out of luck.

The issue of accidentally giving away your life savings can probably be solved by better protections built into end-user software, but the issue of theft is far more pernicious. Some issues, like people generating brain wallets with guessable passwords, can be resolved with education, but as ShellShock proves, the computers that we use on a routine basis are bottomless nightmares of security vulnerabilities.

A friend of mine, a hacker and computer security expert once, was nearly expelled from his university because when given a computer security challenge for a class, he got such deep access to the system it was running on that he was able to set everyone’s grade to infinity. The same friend used to amuse himself by going through open source videogame software and finding and reporting open vulnerabilities. One such vulnerability was an unprotected write buffer in an open source DOOM client. After reporting the bug, he spent several months amusing himself by taking control of various DOOM servers on the Internet and playing dungeon master (by spawning monsters not present in the game, arbitrarily distributing weapons, and altering the maps), until the vulnerability was eventually fixed.

This is fairly benign, of course, but the scary part is that this sort of hacking, with the right education, isn’t particularly hard – my friend is unusually talented, but there are thousands of people in the world who could have found and exploited that bug if they were looking for it, and those exploits (including extremely serious ones like HeartBleed and ShellShock), exist in every piece of software out there. If a talented hacker wants access to your phone or computer, rest assured that they can get it. Even in the absence of a specific virtual assailant, if you run a compromised application (possibly in the hope of getting a free screensaver), your computer can be taken over by malware. No widely used operating system securely sandboxes memory, which means that a program can interfere freely with other aspects of the system and get access to resources it shouldn’t have. All it takes is one mistake, and an anonymous hacker can get complete access to your machine. There’s already Bitcoin-stealing malware, and that problem will only get worse as more and more people start to use Bitcoin. As soon as stealing Bitcoins is more profitable for malware writers than sending spam, we’re going to have a real problem.

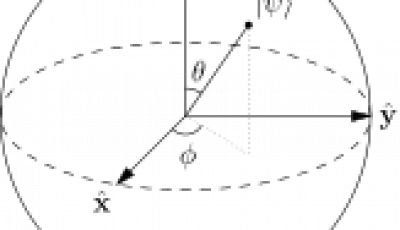

So what can be done about it? Part of the answer is multi-signature cryptography, like the CoPay software implemented by BitPay. If both your PC and your phone are required to make a large transaction, it at least protects you from getting ripped off by a random piece of malware: an attacker who gets access to both probably wants to rob you, in particular, which is a much narrower and less scary threat. It’s not perfect, though. In the long term, it’s probably worth building small dedicated hardware devices with bare-bones, provably-secure firmware that can be trusted with the second key in your two-factor authentication scheme – a second hardware device that you can carry around with you and which you can prove is trustworthy. Another, less likely scenario that I none-the-less hope for is that the rise of Bitcoin, and the first high-profile thefts will raise awareness of computer security, and it might get taken seriously by the public at large for the first time ever, prompting some of the gaping chest wounds in modern operating system to be patched.

For now, at least, most people – at least people who don’t care about the dream, are better off using centralized solutions built on top of Bitcoin, which can offer some of the same benefits as belonging to a traditional bank. For now, at least, Bitcoin “web wallets” (more accurately “Bitcoin banks,” though they prefer not to be called that), are probably the future for all but the most rabidly Libertarian contingent of Bitcoin users. Right now, hackers are more of a threat to the average person than the various sins of (at least first world) governments. If the dream of Bitcoin is going to come true, that’s going to have to change.